By Peter Ferramosca, Cherre Solution Architect

Real estate investment has slowed due to uncertain capital conditions and higher interest rates diminishing potential returns compared to lower-risk options. But even though post-pandemic growth is waning and hybrid work models have impacted offices, opportunities still exist in hybrid neighborhoods, as described by McKinsey in a recent piece about the world’s “superstar” cities.

This piece examines comparable trends in other U.S. markets and micro-markets regardless of size and how investors can effectively assess market potential for targeted, efficient allocation of capital and higher returns.

We’re experiencing a seismic shift in how people live and work, fueled by the pandemic. The markets that will fare better long-term will have a more hybrid or dynamic mix of business types and real estate classes, according to a recent McKinsey report about the world’s “superstar” cities.

In previous projects, I created models analyzing neighborhood dynamics throughout the United States. Those models demonstrated how neighborhoods with certain characteristics – very similar to those that McKinsey calls “Hybrid Neighborhoods” – have achieved higher rent growth since the pandemic. I have also explored in-depth purpose-built mixed-use assets, highlighting their ability to outperform surrounding areas in terms of economic rent and contribute to the growth of adjacent locations. Drawing from my experience and the comprehensive models that I have built, I wholeheartedly agree with the results that McKinsey described.

Neighborhoods that host a combination of office, retail, and residential options become more attractive places for people to live. As more people move to these areas, whether they work from home or in a nearby office:

These synergies create a dynamic within mixed-use neighborhoods where the presence of each component leads to greater success for the others.

The success potential of “Hybrid Neighborhoods” is clear for the global cities analyzed in the McKinsey report, but what about smaller U.S. markets?

As investment volume floods to the U.S. Southeast and Sunbelt regions, these smaller growth markets have something in common – the population of young professionals has increased significantly over the past few years.

The investment popularity of these regions has driven asset prices and rental rates through the roof, to the point that the potential for new investment in these markets as a whole might diminish. However, most other markets still have potential to capitalize on already-established growth nodes with a unique mix of asset types. More interestingly, investors and developers can target growth potential by identifying neighborhoods missing a certain layer of retail, multifamily, or modern and dynamic offices that could make all assets perform better from the presence of the others.

I recently spoke with Komail Khaja, Director of Research for Virginia with Colliers International, about some of Richmond’s high-growth nodes – specifically Scott’s Addition, Manchester, and Libbie Mill. He shared that as nearby metros – particularly D.C. – have become increasingly expensive relative to incomes, Richmond has benefited net positive migration, with the young professional cohort attracted to amenity-rich areas like Scott’s Addition and Manchester. Retail performance has also held strong in these urban and urban-adjacent locales, with Colliers reporting unprecedentedly low vacancies of 2.5% for urban retail through the end of 2022.

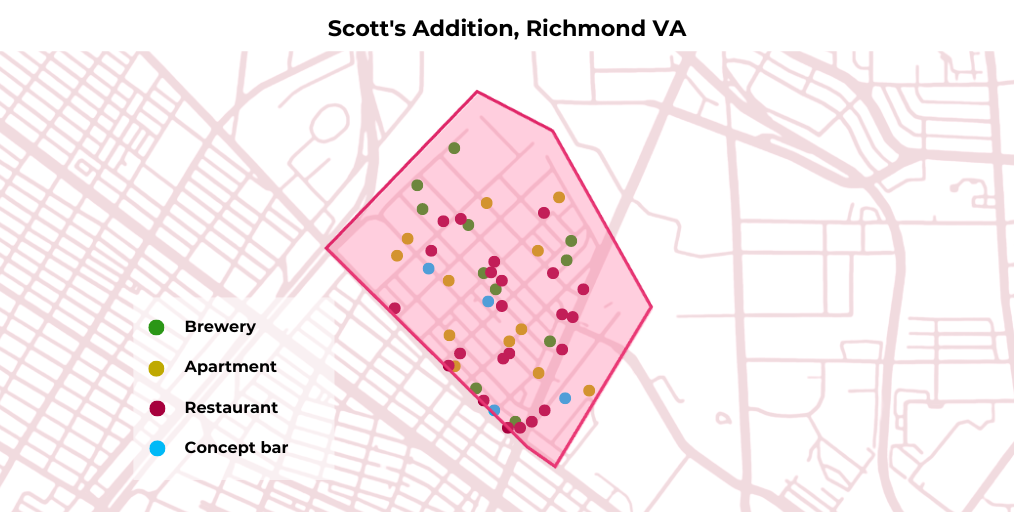

Although others may not consider Richmond to be a growth market, per se, like Raleigh or Austin, I view it as one. I grew up here and have seen the city transform – I remember when Scott’s Addition was all old manufacturing and auto repair buildings, but now this 0.39-square-mile neighborhood has 39 eating and drinking places and over 2,300 apartment units built since 2015. Of those eating and drinking places, 24 are restaurants; 11 are breweries, cideries, or distilleries; and four are experiential concept bars. High-paying employers seeking to attract young talent have followed suit, with companies like middle market M&A advisory Boxwood Partners, financial services firm Agili, and Nasdaq Dorsey Wright all occupying space in the neighborhood.

Scott’s Addition is a testament to how neighborhoods with these types of characteristics present investment and development opportunities in markets across the country. Neighborhoods like Charlotte’s South End, Washington, D.C.’s NoMa, and Bellevue, WA’s Kirkland neighborhood all come to mind as similar examples of high-growth neighborhoods whose combination of asset types propel them to perform better and grow faster than the rest of their respective markets.

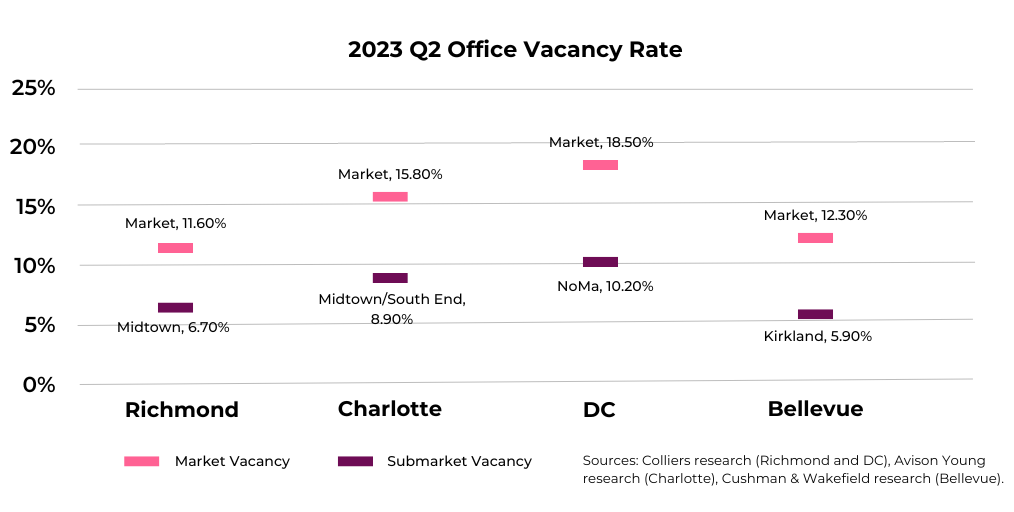

In the current office market, sentiments on demand resurgence (or attrition) vary widely across markets. More interestingly, they vary widely across submarkets within each respective market. Consider Richmond’s Midtown office submarket, which contains both Scott’s Addition and Libbie Mill, along with the comparable submarkets mentioned above. These types of neighborhoods have a surging supply of multifamily, with complementary retail concepts to compel renters to move to the area. Further, the presence of these modern retail concepts and high-quality apartment buildings have given the offices therein an advantage over other areas, as businesses reconsider their office footprint and try to attract and retain new, young talent. As a result, the office component of submarkets with these types of asset composition and growth have much lower vacancy rates compared to their overall respective markets.

If you ask five different people about the future of office demand, you might get seven different answers – but I think most will agree that the flight-to-quality trend has persisted. However, flight-to-quality can be viewed in a couple of different ways – building quality and neighborhood quality, the latter of which McKinsey highlights in particular.

Neighborhoods and submarkets characterized by a better mix of property uses, including modern retail concepts, high levels of quality residential supply, and versatile office components capable of accommodating the uncertain future of office space use should fare better in the future than less “hybrid” neighborhoods as the McKinsey report defines them. Further, areas that are beginning to (or will begin to) convert older, obsolete properties to create a more balanced makeup of assets will generate higher demand for each area as a whole.

I view purpose-built, placemaking mixed-use assets as effectively new live-work-play neighborhoods. They create growth nodes that drive demand for young professional in-migration as access to retail amenities within walking distance provide incentive to live in these hyperlocal areas. And the tenant make-up of mixed-use assets and successful urban “hybrid” neighborhoods tends to have experiential components – think modern concept-based bars and restaurants, yoga and exercise studios, etc. These types of newer retail concepts cater to the young professional cohort to drive renter demand for nearby apartments.

Regardless of whether the office employees in the office component of mixed-use assets actually live on-site, they too benefit from access to nearby retail amenities. As businesses consider the future of their space needs and the labor market remains strong despite economic uncertainty, office space in these types of amenity-rich growth nodes present a way for businesses to attract and maintain a modern workforce whose lives (and priorities) have shifted following the pandemic.

Mixed-use real estate looks different in large established markets versus smaller (and potentially growing) markets, however. Typically, mixed-use in large markets takes the form of urban infill projects – essentially turning a neighborhood into one of McKinsey’s “hybrid” neighborhoods. In smaller markets, mixed-use tends to be urban-adjacent, whether revitalizing neighborhoods like Manchester and Scott’s Addition in Richmond or building an entire mixed-use site like the upcoming Diamond District.

Successful placemaking, live-work-play districts can benefit both the districts themselves and the surrounding areas, but developers cannot simply rely on an “if we build it, they will come” mentality.

Without these considerations, projects might be struck down before development, or worse – reality doesn’t meet expectations and investors and stakeholders take significant losses both in terms of returns and opportunity costs of better-thought-out developments based on each locale.

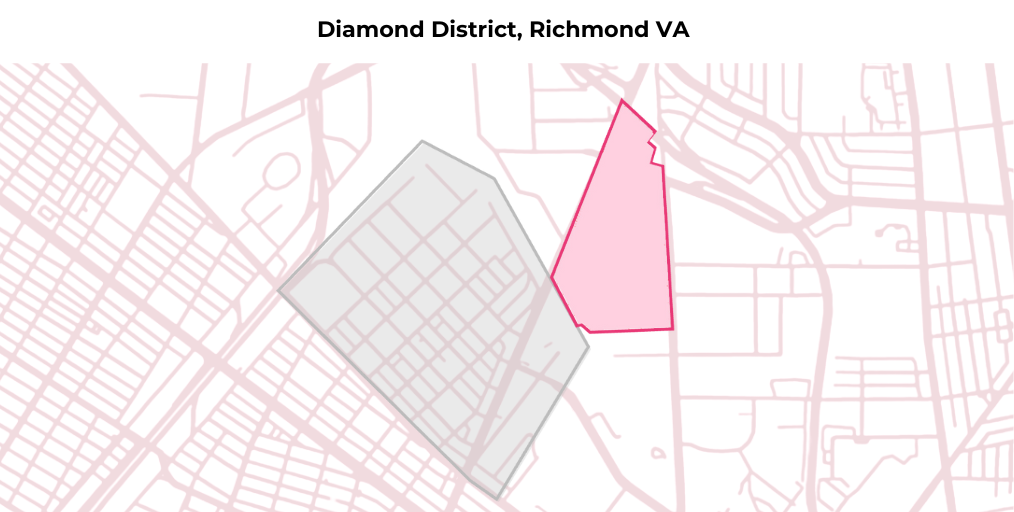

The Diamond District in Richmond is adjacent to Scott’s Addition and will likely augment the growing neighborhood with the addition of a new baseball stadium, a significant amount of new residential units, Class A office space, a new hotel, and integrated retail uses that cater to the space users of the new mixed-use neighborhood.

This project epitomizes concepts described above as a well-planned and forward-thinking approach to mixed-use development that should augment growth in surrounding areas. Had Scott’s Addition and the surrounding retail area not seen such popularity and growth over the past decade, I doubt this new signature mixed-use neighborhood would have even been considered.

In some situations, developing large mixed-use assets involves displacing residents and raising housing costs to the point that those who previously lived there can no longer afford to rent in the new, often upscale apartments that are built. There is a social impact, so new developments must carefully consider stakeholders involved.

While mixed-use developments also often tout themselves on the jobs that they create, it is important to consider the expected wages of the jobs being added to truly evaluate the overall socioeconomic impact of such developments.

Due to these complexities, along with zoning restrictions and other governmental controls, the time it takes for developing placemaking mixed-use assets is typically much longer than any other type of real estate development. This larger time frame could potentially add additional risk compared to standard office, apartment, or retail developments if market fundamentals change over the course of development. In a similar vein, the chance of external factors affecting the real estate industry or a particular mixed-use development itself rises as the timeline from idea to delivery increases.

The themes and conclusions derived from the McKinsey article play out in all markets, not just major global cities. Methods for developing mixed-use assets and hybridizing neighborhoods look a bit different for every market, but common themes still hold.

Areas that combine retail use types, multifamily, and modern office concepts present the most unique growth opportunities across the nation. They are the U.S. version of many European cities whose property makeup is much more hybrid than many cities in the United States.

Lifestyles in the United States have changed following the pandemic. Experiences, convenience, and dynamism in future real estate development and investment are more crucial than ever. Investors must focus on developing a data-driven strategy to identify micro-markets with investment potential, such as these mixed-use neighborhoods and those that are a step away from becoming one.

With Cherre’s AI-enabled Benchmarking Kit — which utilizes hundreds of variables and institutional insight and knowledge — all fed through a proprietary and secure machine learning model, investors can unlock the ability to rank markets and micro-markets based on their own unique strategy and area of expertise to target areas for new acquisitions, showcase a fund’s strategy and return potential backed by data to attract new capital, and even benchmark portfolio or fund performance relative to the assets’ markets.

The investors and developers that embrace these lifestyle changes and act swiftly and carefully through such data-driven approaches will have the opportunity to transform cities, mitigate risks of obsolescence of older assets, achieve significant financial returns, and bring economic growth and stability to the markets in which they operate.

In the old-fashioned game of real estate, forward thinkers that proactively convert structural shifts in market dynamics into data-driven, strategic decision making will be the winners.

The shot clock is running out.

Peter Ferramosca is a Solutions Architect at Cherre. He has extensive experience in real estate and econometric data analysis, specifically as it relates to submarket structural dynamics and their relation to real estate performance. He has advised major institutional real estate market participants in consultative roles with regard to market selection, capital allocation, and real estate investment potential across all U.S. markets.